Trends in Fly Innovation

can we expect new innovations in fly patterns to continue forever?

December 2024

Have you ever heard the old expression that there are no new stories, just seven basic plots and classic tales retold over and over? Hollywood isn't even trying to hide it anymore either, *insert the movie that just came to mind in your head, there's no shortage of examples*. For a long time I've been thinking about that idea as it applies to flies. We're familiar with offshoot patterns and re-brands of classic flies under a flashy new banner, but most new flies are just new variations on older ideas. Truly creative works are hard to come by. These rare flashes of innovation give us movies like Citizen Kane and Being John Malkovich. Fly tying is no different, throughout the ages brilliant steps forward have changed the approach for anglers, or better yet, completely redefined what fly fishing can be. But these offerings are few and far between. When and where will the next one pop up? And can we count on those innovations forever? Can we repeatedly call on the collective group of fly tiers to revolutionize the world with new flies?

First the wet fly, then the revolutionary dry fly. Next was fully dressed Atlantic Salmon patterns, we discovered the power of the nymph, larger terrestrials, other new species, smaller patterns, larger patterns, emergers, articulation, foam, epoxy, the list continues. At each turn the fly fishing world uncovered a deeper well and new ways to apply old ideas. As I recently poured over the pages of "The History of Fly Fishing in Fifty Flies", Ian Whitelaw guides readers through the origins of fly fishing and the disruptive flies that slowly unlocked its mysteries. The book takes us back to the earliest British patterns stretching back to the 15th century and leaves us on a cliffhanger ending in 2006. Though this work is undoubtedly skewed towards a Euro-North American look at flies, with only a brief mention of Tenkara and traditional kebari flies, the book does well to track the timeline of important patterns.

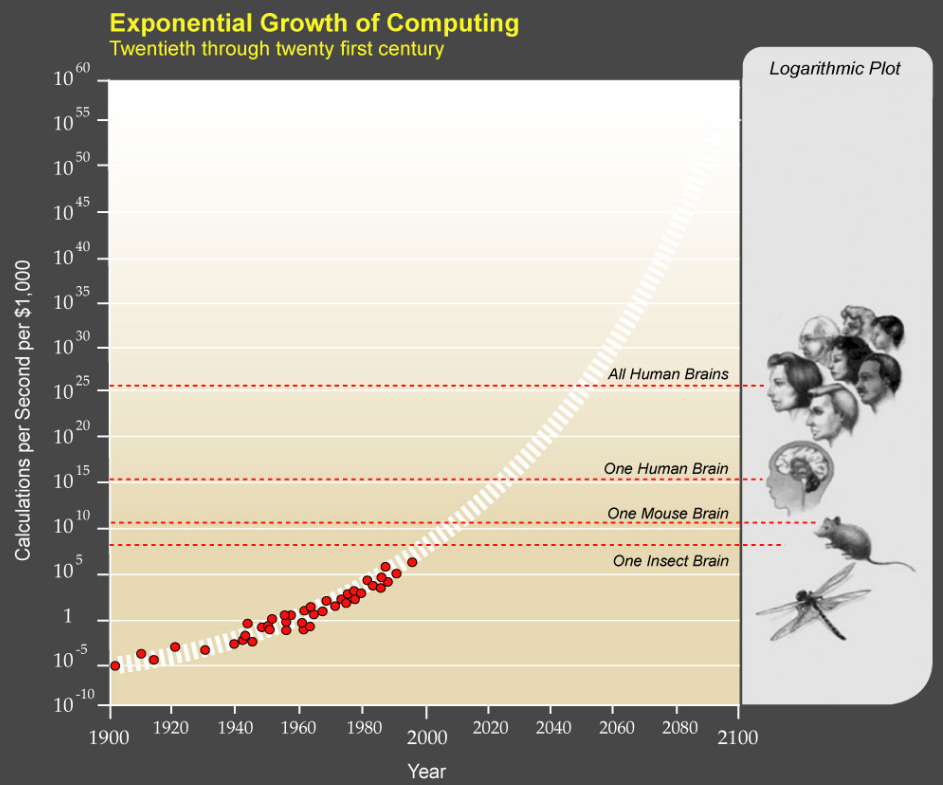

As the book unfolds into the Industrial Age, suddenly flies represented more than just creative expressions, they also represent technology: a means of maximizing catch while minimizing effort. And I started to wonder if fly innovation shares the same exponential growth trend we see in other technologies, like computing.

This peaked my interest because the big question around technology is: can we keep up this exponential rate of innovation? Where, over time, multifold improvements happen sooner and sooner. Back to fly fishing; that's a tough rate to keep up with, especially when you start thinking about the restrictions like match the hatch.

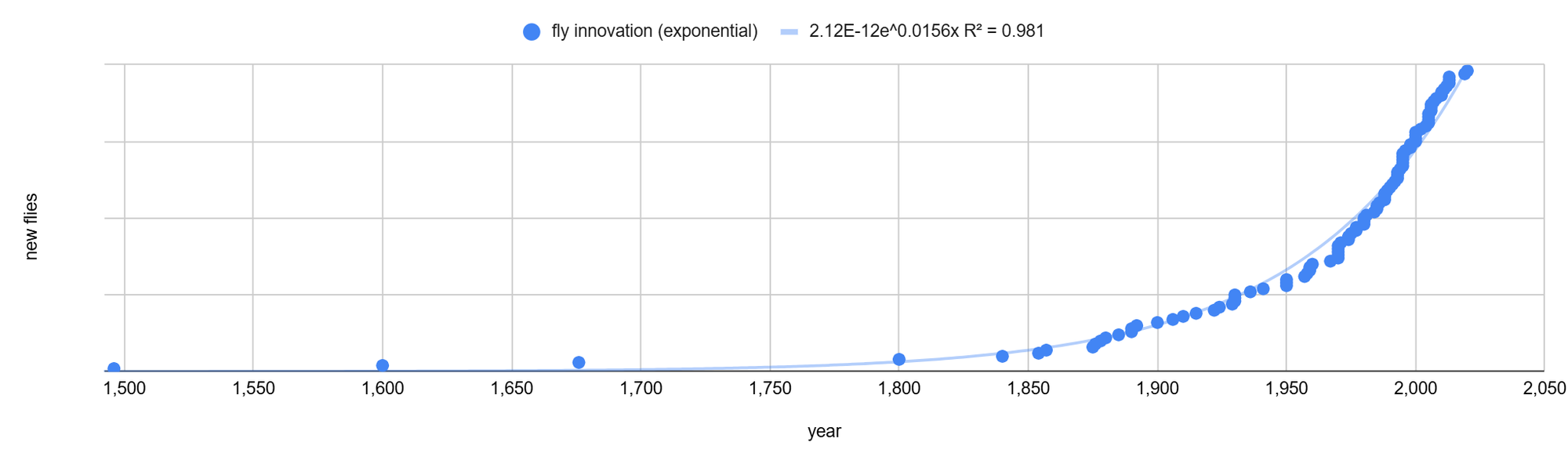

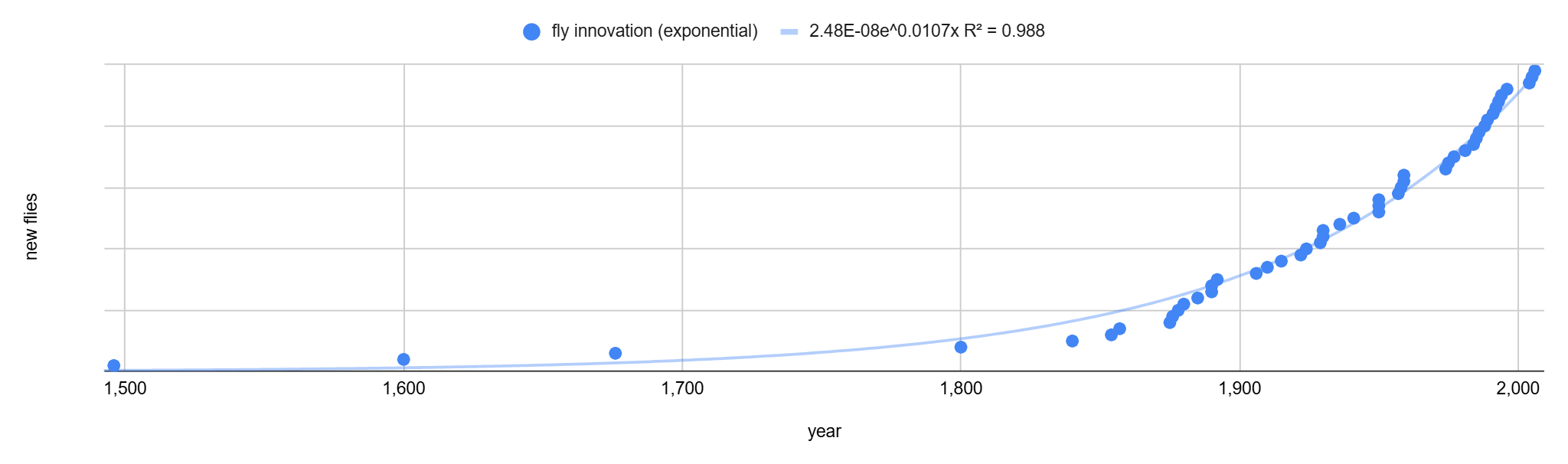

So I started with what we know, Whitelaw's chronicling of the history of fly innovation. Each entry represents a step forward, so naturally as time progresses, shorter intervals between innovative patterns would suggest a similar trend in development: exponential growth. And after the slightest number crunch from his book, we see that so far fly innovation seems to follow the trend of other technology. Important new flies are emerging more frequently.

This alone is pretty crazy to think about, because so many of the consistently reliable patterns are so much older than I ever expected. The Adams dates to 1922, Bass Poppers date to 1915, and soft hackles go back into the 1800s. Even outside of trout, the Crazy Charlie is a 50 year old pattern (1977), and Lefty's Deceiver is 65 years old (1959). Each of those flies absolutely crushes in the modern era. Add the Clouser Minnow in 1988 and you're setup for almost anything.

But at some point we've covered all the hatches, all the baitfish profiles, we can get our flies to swim like real bait, and even know enough about are target fish to recite their habits backwards and forwards. So this exponential trend can't continue. It just can't...

Then again, by 1959, trout anglers could craft a full box with Dave's Hoppers, Pheasant Tails (1958), Elk Hair Caddis (1957), Muddler Minnows (1936), Prince Nymphs (1930), Adams (1922), and even some Mickey Finn's (1890). That's a fine box for most freestone rivers even today, maybe even all you'd need.

But fly fishing expanded it's reach too. New venues: tailwaters, lakes, reservoirs. New species: warmwater ponds, carp swamps, saltwater flats, jungles, deep ocean. New places with new idiosyncrasies. New times: winter, night, runoff. And running right alongside: new rods, reels, more roads, better travel, sonar. Information, the internet.

Doubt remains, see Whitelaw stops with the latest entry dating to 2006, the Bionic Bug, a pattern from one of the newer frontiers, New Zealand. So, I spend an afternoon ignoring work and pouring through commercial fly catalogs to pick up some of the pieces Whitelaw missed. (He didn't include the Woolly Bugger, I mean what's that?). The list was updated to better represent the breadth of species that are commonly seen in social media posts these days, and the additional flies that best represent the innovators in each category. Plus many were missing from the trout category too. My rules were to try to dig up the original profile, original concept, or original material that defines the entire category. Most foam terrestrials wouldn't have developed without the first entry, presumably the Chernobyl Ant, so that one flies covers an entire catalog of foam entries. The bonefish gotcha is a great fly, but it's just a Crazy Charlie with a different wing material. Same profile, not (necessarily) innovation. Don't fight me. There's also a difference between the original fly and any new applications of that fly. The Clouser Minnow's effectiveness in a new fishery doesn't give it another entry on the updated list, just speaks to how inventive the original concept was.

Here's an updated list of flies not mentioned that really should have been.

| Year | Fly | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | Killer Bug | Need an entry for sow bugs and scuds |

| 1960 | Sheep Creek Special | Unique stillwater design with hackle in aft to push water |

| 1967 | Woolly Bugger | Universal fly |

| 1970 | RS2 | Tailwater staple needs representation |

| 1970 | San Juan Worm | Worms are essential trout food |

| 1970 | Reverse Spider | Unique movement with unique profile unlike anything else |

| 1970 | Surf Candy | New profile and material |

| 1970 | Mini Puff | Unique color and profile in bonefish flies |

| 1971 | Flashtail Whistler | New material and large fly footprint for pike or other predators |

| 1974 | Sparkle Pupa | LaFontaine's work on caddisflies leads to this fly |

| 1977 | Dahlberg Diver | New diving motion in the surface/popper world |

| 1980 | Blood Dot Egg | Every salmonid lays and/or eats eggs |

| 1980 | Bonefish Bitters | Rubber legs, epoxy head, unique profile |

| 1980 | Shipman's Buzzer | Unique foam application for emerger |

| 1985 | Spoon Fly | Spoon in fly form |

| 1988 | Gurgler | Gurglers are iconic |

| 1988 | Serendipity | New profile and material use in emerger |

| 1990 | Chernobyl Ant | Kick-started the foam terrestrial category |

| 1990 | Ray Charles | Redefines sow bug, scud profile |

| 1993 | Blob | Innovative attractor/lure |

| 1993 | Intruder | Iconic swinging fly profile, defines a whole category |

| 1995 | Pat's Rubber Leg | Rubber legs, large profile nymph |

| 1995 | Flexo Crab | Material creates realistic, lightweight crab profile |

| 1995 | EP Baitfish | Inventive material capable of realistic baitfish profiles |

| 1995 | Deer Hair Mouse | Kick-started mousing |

| 1995 | Schminnow | Saltwater Woolly Bugger |

| 1998 | Mop | New material and profile unlike other nymphs |

| 1998 | Gummy Minnow | New material and silhouette |

| 2000 | Circus Peanut/Peanut Envy/Sex Dungeon | Kick-started large fly articulated streamers |

| 2000 | Zoo Cougar | Kick-started large profile floating streamers on sinking lines |

| 2000 | Ismo Pupa | Unique Swedish balsa wood caddis dry fly |

| 2000 | Avalon Permit Fly | Bead chain belly for weight |

| 2002 | Perdigon | Smooth water-resistant epoxy body for deep nymphing |

| 2005 | Mercer's Missing Link | New dry fly profile |

| 2005 | Balanced Leech | New profile and tactics for stillwaters |

| 2006 | Game Changer | New movement and fly design |

| 2006 | Headstand | Represents the headstand concept for carp flies |

| 2007 | Hippie Stomper | New use of foam: mini attractors |

| 2008 | Murdich Minnow | New streamer profile |

| 2010 | Squirmy Wormy | New material, new movement |

| 2010 | Bisharat's Pole Dancer | Spook equivalent in fly pattern |

| 2011 | Mole Fly | Tailwater emerger with CDC |

| 2012 | Grim Reaper Bass Fly | Finesse jigs translated to fly fishing |

| 2013 | Two Bit Hooker | Multiple bead entry on slim nymph |

| 2013 | McTage's Foam Trouser Worm | Foam rising tail on headstand chassis; new concept |

| 2019 | Maddin's Scorpion | Surface streamer, combining foam terrestrial and baitfish profile |

| 2020 | Slick Willy | Kelly Galloup's new baitfish prodigy |