Attracting Rises from Trout

Wisdom from a forgotten book: Why do trout rise to a dry fly? Exploring LaFontaine's lost ideas on attractors

November 2024

The road runs along the water as we turn upstream. I say, "Count the nymphers" as we rock back and forth matching the bends.

We takes note out loud, "One, two, there's another... it's everyone..."

Tying this winter? Check out the selection at AvidMax, our go-to shop

The angling world is in the midst of a subsurface revolution. Between the articulated streamers and the widespread emergence of Euronymphing tactics, anglers are more focused than ever to on dunking flies. Though I don't have material evidence to back it up, I can't help but notice that this refocus in tactics has come at the cost of the dry fly. First noticed in fly shops, nymphs out number hackled alternatives, and corroborated on social media, beadheads abound. Outside of the grasshopper, it feels like anglers have lost the subtle touch of charming a trout to the surface. Or at least the will to, in my neck of the woods.

Chasing numbers may be partly to blame, once you see an angler recognize the power of the perdigon, you can spot a certain craze in their eyes. I've seen it in myself. The revelation for how many more fish are now at your finger tips, it's too much power. But to pull a fish to the surface takes a snake charmer. The food isn't just delivered already at mouth level, it requires a trance, an upward pull. Has the dry fly been relegated to the naive fish of tiny creeks and alpine lakes?

Imitation vs Attraction

Half of the dry fly world is based on imitation, and is straight forward enough. Match color, size, and profile in a fly and present to fish rising for insects. That part is easy... Yet, on quiet day with no sign of hatching bugs, how many still choose a dry fly for prospecting? Or even have the confidence to approach that water with dries?

"Imitation is creative laziness" - Gary LaFontaine

Enter attractor patterns and our protagonist exploring why trout rise, Gary LaFontaine. In his 1990 book Dry Fly: New Angles, Gary applies analytical methods to breakdown and assess what repeatedly triggers rises. He outlines ideas about which styles of flies work best for different water types, breaks down the sequence of visual cues fish pick up on during their rise, and outlines a color theory to refine fly color based on surrounding light. Each idea backed by field observation (including scuba) and scientifically inspired trial and error. It's truly an eye opening book and still relevant, but somehow the ideas feel lost to the past. I've never heard any of the ideas from the book anywhere else and yet I was still convinced by the logical tactics Gary outlines. So I wanted to highlight the lasting ideas and bring them back to the forefront. We can't leave such a detailed entry to the crossover world of angling/science shelf ridden and dusty.

When... if... fishing dries, how do you pick an attractor? Is it on a whim or is it based on any logic? For me, it's mostly what I see first when I open my fly box. Does that approach work? Sure. But it's a shotgun blast. Cast until it's proven right. What if there was a better playbook to pick attractors.

Matching Attractors to Water Type

Picture your typical creek, pocket water galore. You can drop a cast in hundreds of little holding lies and fish cooperate by eating a wide variety of options. Now transport yourself to the opposite type of water, usually found on larger rivers: long quiet runs/pools. Maybe not the water you picture for the standard attractors like a Royal Wulff or Humpy, and often those flies don't work as well in this setting. So, maybe this water calls for a different style of attractor.

In the fast water Gary suggests that heavily hackled flies give a distinct imprint on the waters surface thanks to surface dimpling from the hackle, and with little time to react, trout are mostly responding to this depression in the water, illuminated by a change in light surrounding the fly . But that same dimpling seen in slower water merely gets noticed, and doesn't necessarily entice a rise. Fish have time to inspect a fly's secondary characteristics and often the heavily hackled attractors don't close the deal for weary pool residents. In the slower water you need flies that sink deeper into the surface film to convert the initial pulling traits of the fly into saving traits that lead to the full rise.

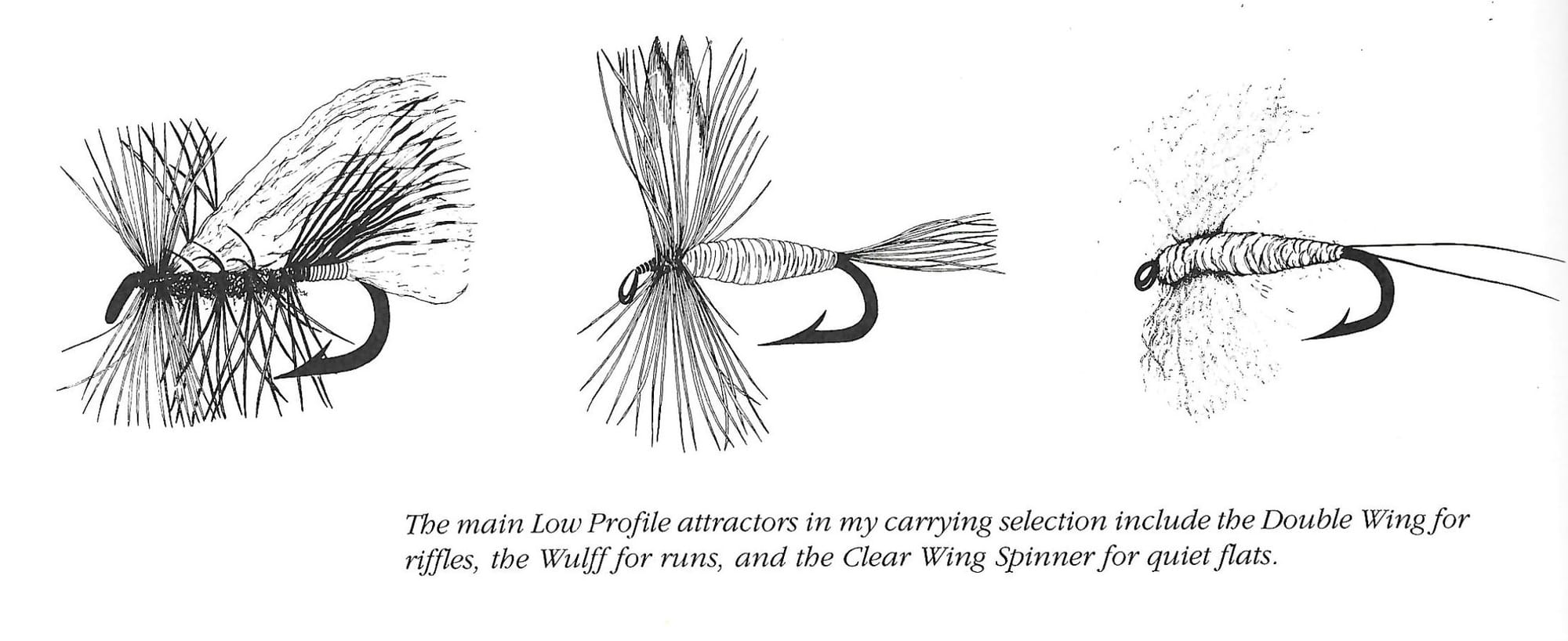

For fast riffles, Gary's favorite is his Double Wing, and other flies that present a wide noticeable profile. For moderate runs, Gary likes Wulffs and favors tall flies that play off of the mirrored reflection of a fly on waters surface, while on slow water, attractors should ride low in the column. Here he favors oversized spinners and odd-ball patterns like the Mohawk.

Interestingly, the Chubby Chernobyl fits all the above rules considerably well: wide profile visible in fast water, low riding for slow water, even the tall wing for moderate runs.

Stealth and Casting

Microdrag was still a known issue in 1990, and as a result LaFontaine is clearly no fan of long casts. Instead, he favored a stealth approach, trying to keep casts to 15 feet or less. But beyond that, the entire process should be slowed down: casting frequency, movements. He elaborates that during hatches, fish (at least in his region) could count on seeing an insect about every twelve seconds. Any slower than that and he found fish were not exclusively keyed into the hatching bug. And if you find yourself repeatedly casting over the same fish, a slow rhythmic cadence of casts can help relax a weary fish, as a means of “micro-desensitization”. As he explains, fish are reactionary and once you’re deemed harmless, fish quickly refocus their attentions on their immediate surroundings. They live in a river after all, and constantly need to pay attention upstream. The slower your approach, the less noticeable you are to fish–even when they can see you.

Also interesting, he explains that for fish that may be willing to eat grasshoppers, cast only every 30 seconds. Even without true abundance, you may be able to create an illusion of abundance that eventually entices the fish.

Color Attraction Theory

Where Gary really sends things to another level is when he considers how light interacts and alters the visual characteristics of a dry fly. It's more than just dark day, dark fly; bright day, bright fly.

The first most important lesson he shares is to understand that the color appearance of your fly changes throughout the day. Sunrise, midday, and sunset each have different visual qualities. Plus river substrate, surrounding streamside rocks, and vegetation can further alter light… and therefore your fly.

Here Gary explains his theory first hand.

TLDR: The Color Theory

- Color of surrounding light affects intensity of fly color

- Intense colors attract trout

My first reaction to this simple theory was strong skepticism. In fact, I was so doubtful I enlisted some of our crew to conduct our own field experiments. We’re probably going to get into that in its own article, but based on those tests and some additional book-worming, I was able to better understand the principles his theory is based on. Though I don't think he explains the natural phenomenon as thoroughly as he could have, there is a scientific basis to his thinking. The low light of sunset filters light through the atmosphere to favor reds, and the sun’s natural output produces mostly yellow and green light than can favor anglers midday with yellow flies or green flies fished along grassy banks.

He also uses the color theory to hypothesize why the royal color (peacock herl + red tinsel) scheme is so effective. The red attracts at times, and in the exact opposite setting, the green is activated. Even under dark skies, where colors are muted, these colors still have a prominent dark profile.

Wiser Than Me

I distinctly remember one encounter early in the morning on a popular tailwater where us young nymphers were arriving just as the more experienced dry fly guys were calling it a day. Through our brief exchange I learned that these veteran anglers had only fished to early morning risers and were off to greener pastures with no attempt at nymphing under a climbing sun. I found this baffling and couldn't understand the rigidity in their approach. But years later, reflecting on that exchange I have a new appreciation for their commitment - a different skillset, one that takes finesse. And one where inflexibility (stubbornness to continue fishing dries) can lead to discovery. What else can we get trout to rise to? We won't know unless we try. At least we have LaFontaine to guide us into that unknown.